The gases helping us adapt to climate change are themselves a leading driver of the crisis.

As climate change intensifies, the world will increasingly lean on air conditioning to cope with extreme heat. Today, over two billion air conditioners supply global cooling needs. This number will triple by 2030.

Almost every air conditioner in operation today uses synthetic refrigerant gases to function. The most popular refrigerants today are hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which replaced previous generation, ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) in the 2000s.

While HFCs are ozone-friendly and efficient refrigerant chemicals, they are also greenhouse gases thousands of times more potent than CO2.

The most common HFC used in AC units today, R-410a, has 2,088 times the climate impact of CO2 on a ton-for-ton basis. R-32, an HFC specifically engineered to have lower global warming potential (GWP), is still 675 times as harmful as CO2 by the same metric.

Managing the Installed Refrigerant Bank

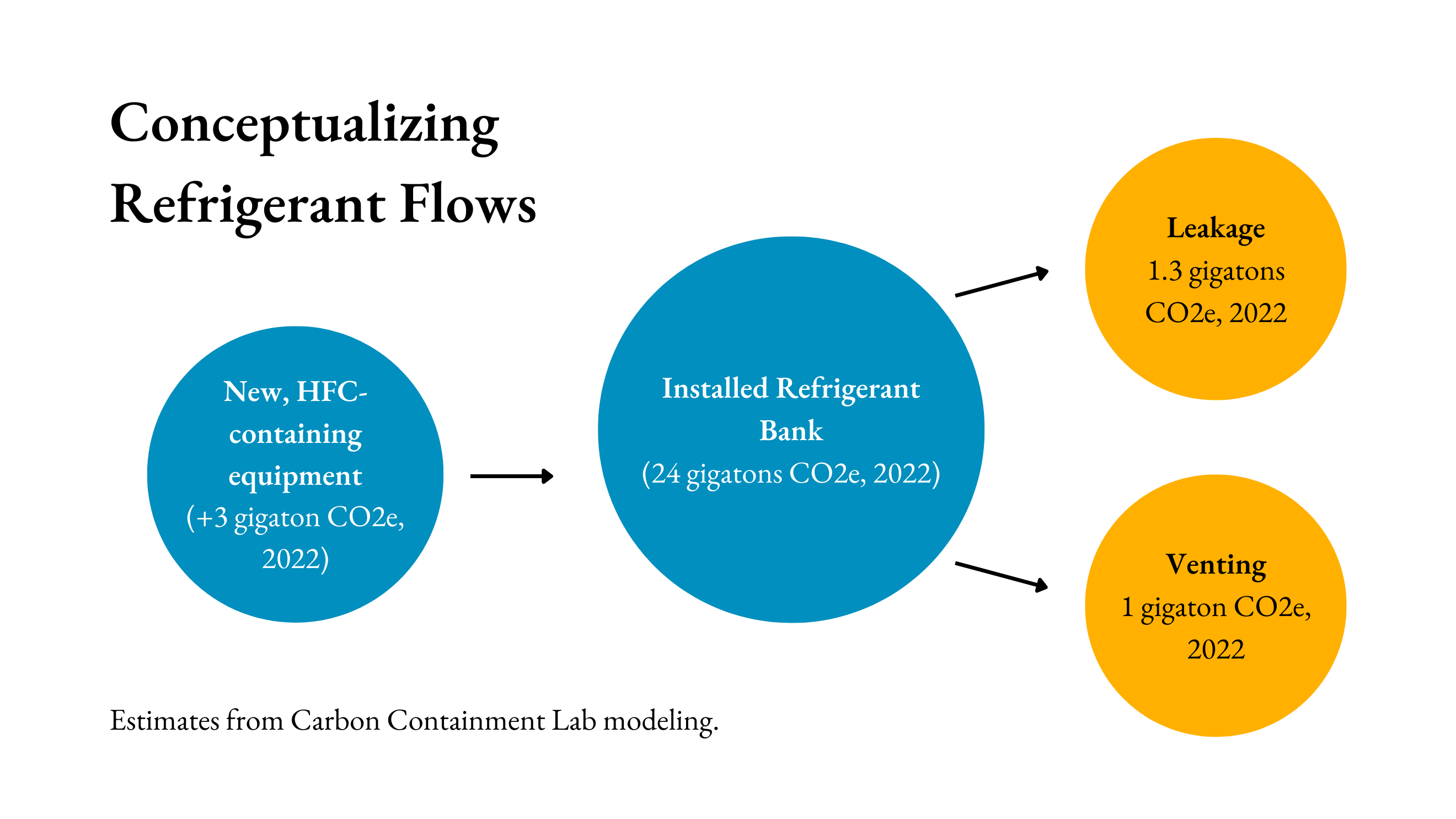

Potent HFCs and exponential air conditioning growth are a recipe for a serious climate threat. The aggregate amount of refrigerant in the world’s cooling equipment today (often called the “installed refrigerant bank”) totals 24 billion MTCO2e – equivalent to the annual emissions of 5 billion gas-powered cars.

Gases such as HFCs wouldn’t harm the climate if they stayed locked away in air conditioners and refrigerators. Unfortunately, they are being emitted in large quantities each year. Cooling machines steadily leak during their operating lifetimes. Then, at the equipment’s end of life or during routine maintenance, technicians or equipment operators often vent (i.e., release) the remaining refrigerant into the atmosphere all at once.

Our models estimate that, between now and 2050, HFC venting from air conditioners alone could total 33 billion MTCO2e -- more than the emissions from all US cars in the same time. The gases helping us adapt to climate change are themselves a leading driver of the crisis.

International Treaties Won't Stop Near-Term HFC Use

Policymakers around the world are moving to curb HFC emissions. 138 countries (including the United States, as of last October) have ratified the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty to phase down the production and use of HFCs across the world. While a significant win for the climate, the Kigali Amendment primarily focuses on bringing climate-friendly technology to market – not dealing with the HFCs already in existence.

Furthermore, the Kigali Amendment comes into force slowly in developing countries, where lifecycle refrigerant management practices are non-existent and air conditioning adoption is growing the fastest. That means that, despite international progress, most air conditioners for the foreseeable future will still be using high-potency HFCs. Even with full implementation of the Kigali Amendment, experts project that 91 billion MTCO2e in refrigerants will be produced and/or consumed through 2100.

The Problem with Venting

Refrigerant venting has been a particularly tricky issue for policymakers to tackle. Most countries, including the United States, nominally prohibit venting. But enforcement of these regulations is rare and infeasible in practice. Refrigerant is colorless and odorless, making it difficult to detect refrigerant venting. There are also few incentives for responsible refrigerant recovery: most developing countries do not have legal end markets for recovered refrigerant, making it impossible for compliant technicians to be compensated for their services.

Today, industry estimates that close to 90% of refrigerant in end-of-life equipment is vented to the atmosphere in the United States. In the developing world, the number is close to 100%. In a country such as Indonesia, we estimate that refrigerant venting could emit close to 1 billion MTCO2e through 2050. That’s more than the projected electricity use emissions of the entire city of Jakarta in the same time frame.

Leveraging the Carbon Market

Carbon markets can provide a critical source of funding to the mitigation of HFC emissions. For decades, major voluntary and compliance carbon credit registries have approved the destruction of ozone-depleting refrigerants such as CFCs, preventing close to 25 million MTCO2e of emissions. Best practices for HFC recovery and destruction are identical to those for ODS, and amendments to existing methodologies approving HFC destruction are in the pipeline.

So how does refrigerant destruction work, and how can it generate a carbon credit? Under this model, technicians, incentivized by project developers, recover HFCs at end of life instead of venting the gas into the atmosphere. Project developers aggregate and incinerate the refrigerant at extremely high temperatures (for example, in a cement kiln), permanently destroying the gas and preventing it from ever reaching the atmosphere. Developers then generate carbon credits equivalent to the amount of refrigerant destroyed – all which would otherwise have been emitted – and sell them to buyers. This process creates a market for recovered refrigerant. No existing carbon credit standards for HFC recovery and destruction exist, but we've been looking into one promising startup, Recoolit, that claims to collect and destroy end-of-life HFCs in Indonesia.

Provided that projects follow existing and forthcoming standards (developed by groups like UNEP and AHRI, in addition to registries like ACR and Verra), the Carbon Containment Lab considers HFC destruction carbon credits to be both high-quality and desperately needed.

There’s still a lot to be done before HFC recovery and destruction are common practices worldwide. In future posts, we’ll dive deeper into explaining the challenges of building the market and infrastructure required to create an HFC management ecosystem and sketch out the Carbon Containment Lab’s plan to help. We'll also outline other critical pillars of lifecycle refrigerant management, such as refrigerant leak detection and reclamation. But the science and data are clear: refrigerant destruction offers an unparalleled opportunity for additional, cost-effective, and permanent mitigation now. Tackling refrigerant venting is one of the highest impact – and most overlooked – climate solutions available to us today.

.jpg)