As described in the first blog post in this series, geochemical carbon dioxide removal (CDR) pathways are numerous and show much promise. How much promise? This is what a well-designed regional life cycle assessment can tell us.

This blog post reviews the motivation and design behind a recently published life cycle assessment paper and tool produced by the CC Lab and partners to assess ex-situ mineralization systems using reactors.

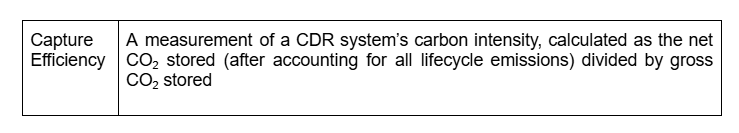

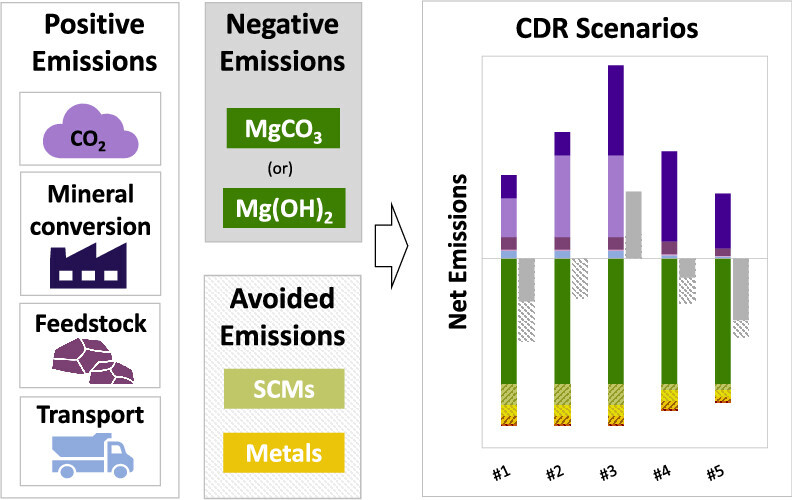

Among geochemical carbon dioxide removal pathways, reactor-based mineralization has important advantages. Chief among them is that—besides its own CO2 removing, negative emissions potential—its co-products can enable avoided emissions in other industries. Jointly considering both negative and avoided CO2 emissions suggests that these CDR systems can achieve capture efficiencies exceeding 100% in some scenarios. In fact, mineralization can be a highly effective and durable way of removing carbon dioxide - or not at all. The extent to which this is so is both technology and regionally dependent.

Another advantage of reactor-based mineralization systems is that they facilitate accurate carbon accounting. Given that they involve processes that occur in closed, engineered systems that allow a high degree of human control, it is relatively easy to quantify the carbon-intensity of each stage involved in the process of storing one metric ton of CO2. In contrast to more open geochemical CDR approaches like enhanced rock weathering (ERW), this allows the capture efficiency of reactor-based mineralization systems to be calculated more accurately and robustly.

However, these advantages come with trade-offs. Reactor-based mineralization systems typically require energy for the preparation and transportation of the mineral feedstock, for CO2 capture, and for the mineralization process itself. These significant sources of positive CO2 emissions make the capture efficiency of reactor-based mineralization systems highly dependent on site-specific conditions, like the carbon-intensity of the electrical grid and the distances that feedstocks or products must be transported.

Life Cycle Assessments Can Help Us Understand the Trade-Offs

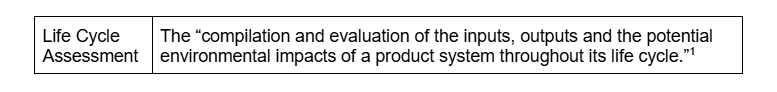

We developed a parameterized life cycle assessment (LCA) to provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating reactor-based mineralization systems by accounting for their positive, negative, and avoided emissions. This is now published here.

Previous LCA studies of reactor-based mineralization have largely focused on within-gate processes, narrowly focusing on the direct industrial emissions associated with the mineralization stage. When avoided emissions are included in the system boundary, reported capture efficiencies vary widely, ranging from net CO₂-positive (i.e. systems emit more CO₂ than they remove) to more than 100% CO₂-negative.

To better understand the potential of reactor-based mineralization as a CDR pathway, the CC Lab designed an LCA study and tool that:

Considers the full range of possible co-products, incorporating potential avoided emissions from their uptake in other sectors;

Extends from cradle to grave, including the carbon intensity of every step in the CDR system, from feedstock mining and CO2 sourcing to the disposal of byproducts; and

Is parameterized to incorporate site-specific details and accurately reflect the resource-intensity of the processes involved across diverse contexts.

The CC Lab Parameterized LCA Tool

As a cradle-to-grave LCA, this tool strives to capture a complete picture of the capture efficiency of the mineralization systems considered. (See Figure 1.) It considers emissions from every stage in the CDR system, namely:

The mining, processing, and transportation of mineral feedstock;

The sourcing of CO2 from direct air capture, point-source capture, unprocessed flue gas, or the ambient environment;

The mineralization pathways considered; and

The transportation of coproducts to be integrated into other industrial processes (contributing to avoided emissions) or discarded in a landfill.

Mineralization Processes

Our LCA tool models two mineralization processes—direct and indirect reactor-based mineralization. The direct approach involves the dissolution and reaction of feedstock with CO2 in high pressure and temperature reactors. The indirect approach involves an electrochemical pH swing reaction that produces brucite, a mineral that can react with natural levels of atmospheric or dissolved CO2.

Co-product Displacement and Avoided Emissions

One of the most critical factors driving the high capture efficiencies of reactor-based mineralization systems is the presence of recoverable co-products that can displace more carbon-intensive inputs in other industries to generate avoided emissions. Co-products can also help strengthen project economics, providing revenues that are less reliant on carbon markets or subsidies.

Our LCA tool considers the possible uptake of silicate (SiO2) and magnesite (MgCO3) co-products in the cement industry as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Replacing a share of Portland cement with SCMs can help decrease the overall carbon intensity of cement mixtures, thereby generating avoided emissions in the cement manufacturing process.

Metal recovery within the reactor-based mineralization process is a second potential source of avoided emissions. The LCA tool considers the displacement of upstream emissions from conventional production processes for metals potentially present in the mineralization feedstocks—including those that are abundant (iron, chromium, nickel) and those with high economic value (cobalt and platinum group elements).

A Flexible LCA Framework for Strategic CDR Deployment

Our goal in designing this LCA was to calculate rigorous and comparable capture efficiencies for different reactor-based mineralization systems across a variety of scenarios and locations. To this end, it was designed in a way that is mineral and technology agnostic. This flexibility allows users—whether researchers, startups, investors, policymakers, or industrial partners—to compare different mineralization technologies across diverse contexts and gain insights that can help guide strategic and effective deployment of these CDR systems.

We decided to release the tool along with the paper to speed up others’ analysis of their own systems and regional applications.

In the third blog post in this series, we will share the high level insights created by this tool when applied to the Twin Sisters olivine deposit in Whatcom County, Washington.

Find the CC Lab’s LCA tool in the Environmental Science & Technology journal:

Footnotes

1 “Environmental Management — Life Cycle Assessment — Principles and Framework,” International Standards Organization, accessed December 9, 2025, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14040:ed-2:v1:en.

2 Ostovari et al. note that this narrow scope can obscure the broader climate implications of these systems. See Hesam Ostovari et al., “Rock ‘n’ Use of CO2: Carbon Footprint of Carbon Capture and Utilization by Mineralization,” Sustainable Energy & Fuels 4, no. 9 (2020): 4482–96, https://doi.org/10.1039/D0SE00190B.

3 Thoneman et al., in their meta-analysis of reactor-based approaches, highlight the resulting challenges for comparability across studies. See Nils Thonemann et al., “Environmental Impacts of Carbon Capture and Utilization by Mineral Carbonation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta Life Cycle Assessment,” Journal of Cleaner Production 332 (January 2022): 130067, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130067.

4 Ostovari et al., “Rock ‘n’ Use of CO2.”

5 Allan Scott et al., “Transformation of Abundant Magnesium Silicate Minerals for Enhanced CO2 Sequestration,” Communications Earth & Environment 2, no. 1 (2021): 25, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00099-6.

-1768404394.jpg)